[The header image was AI generated. I only wish I could draw that good.]

A couple of years back (more or less) I wrote a little on Protagonists. As a refresher, here are the terms as I see them as a Writer, Critic, and in general mad man:

- Plot: A series of Action/Reaction events that form a story.

- Protagonist: Character who’s choice has the greatest effect on the Plot.

- Antagonist: Character that either opposes the Protagonist or is opposed by the protagonist. A proper Antagonist has a greater effect on the Plot than most.

- Hero: The moral center of the Plot. They might not be the Protagonist, as that role isn’t a moral choice.

- Villain: No shock, but a character that is the opposite of the Hero. Someone actively doing harm. They can even be the protagonist, as that role isn’t a moral choice.

- Unfortunate Soul: Character who endangered by the Plot’s events that for reasons can’t do anything. They are never a Protagonist or an Antagonist, as they’re choices have little to no effect on the Plot.

Let’s add one final term, just for fun:

- Force: An element that can drive the Plot that doesn’t have the agency of a Protagonist or Antagonist. It makes no conscious choice for or against, but actively effects the Plot.

That’s seems like a fine sampling.

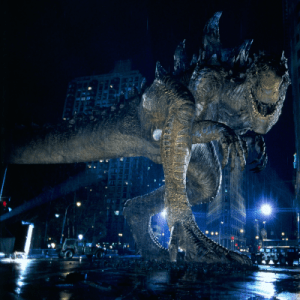

Let’s look at a few stories, see how this shakes out. As I am who I am, we are looking at the three Godzilla movies that share the name Godzilla. Starting with the 1998 classic Godzilla.

Don’t make that face. It’s unbecoming.

Spoilers, for what it’s worth.

The Protagonist in Godzilla 98 is Nick Tatopoulos. He’s the one who makes all the choices that matter. He wants to stop Godzilla from causing destruction.

Opposing him as the Antagonist is, of course, Godzilla. All Godzilla wants is to roam about and be the best little monster it can be. Towards the end, with its offspring slaughtered, it actively tries to harm Nick. The size of its choices matter.

Ahem.

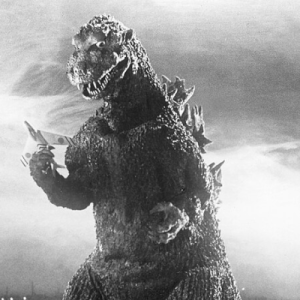

With Godzilla 14, things get interesting.

The Protagonists in this story are the bug like Muto. Everyone reacts to their choices. It doesn’t matter how they’re destructive. Being the Protagonist isn’t a moral choice, and every choice they make moves the Plot forward.

That said, once again the Antagonist here is Godzilla. He doesn’t want the Mutos to get what they want. They threaten his existence and until they stop, he won’t stop, either.

Now where does the human character, Brody, stand here? He’s the Hero. His actions, while important, don’t change the basic conflict between Muto and Godzilla. He helps Godzilla deal with the situation, unquestionably. But when everything is said and done, he does nothing that changes the Plot. If he wasn’t involved, the conflict would have continued and ended just fine without him.

Albeit perhaps not as happily for the world.

Now if you thought that last bit was wrong headed… well you ain’t heard nothing yet.

The Protagonist in the original Godzilla is the character you see the least: Daisuke Serizawa. Standing against him is the Antagonist… Hideto Ogata.

Yeah. That’s right. Godzilla doesn’t matter in his own first movie. at best he’s a Force.

Isn’t that wild? But hear me out.

What Godzilla is is unimportant. He doesn’t have to be a radioactive dinosaur. He could be anything from a giant octopus (which he almost was) to radioactive sludge.

What matters is that he’s a problem that needs solved.

Serizawa has the solution to that problem. It is his choice that matters the most in the movie. To refrain from acting means the threat continues unhampered. Acting, on the other hand, might unleash a far worse threat. In fact, Serizawa is pretty certain that it will.

Ogata, however, opposes this. He sees only the threat before them and forces Serizawa into a decision. And, in my humble opinion, that decision is the worst possible choice.

To reinforce this, remember there is only one scene between Serizawa and Godzilla. Godzilla, at the time, is minding his own business. His threat, while real and present, is also theoretical at that point.

As I’m throwing cod theory about, let me say that the real antagonist should have been Emiko Yamane. Ultimately she’s the one who betrays Serizawa on so many levels. But that’s expecting a little much from a film out of the Fifties.

Now that was fun. Might go back to this little thought experiment at another time.